(A lecture-testimony to the fellows of the 2nd Lamiraw Creative Writing Workshop in Calbayog City, Samar, 22-24 September 2005)

ON THE WAY to this workshop, there was no turning back to the facts revealed in the headlines of Cebu's newspapers: A policewoman stationed at the Women's Desk (where the complaints of abused women are heard) was murdered by her own husband. A 12-year-old girl was also killed after her own father and her uncle allegedly took turns raping her. Masked men, in vigilante fashion, remained on the loose after leaving corpses of suspected criminals. Meanwhile, the governor of Cebu had joined the Cardinal's call for an end to the bloodshed between two warring fraternities. On the political front, the city mayor and a congressman from an adjacent city were locked in a squabble on jurisdiction over a reclaimed strip of real property. Elsewhere, of course, the primetime news had been cranking up cliches ad nauseam about the doggone state of our nation: leadership crisis, the circus in Congress, a ping-pong of allegations about corruption, protests galore, and restlessness about an impending oil price increase.

These news, come to think of it, are a rehash of a reality reported in newspapers, say, twenty years ago. The personalities may have changed, but the circumstances remain. Talk about bad news, and there's really nothing new about this notion of badness under the sun: rotten politics, reckless policies, regrettable interpretation on the concept of public service.

Obviously, some lessons we were supposed to know in kindergarten have been outgrown or, worse, forgotten. From these horrible happenings, certainly, we have not yet learned. Or how come we seem cursed to repeat all these things too bad and too boring as they remain true in our times. Strange, indeed, in the face of this so-called enlightened times in the summit of human achievement, in this era of information technology. So strange that the recurrence of this phenomenon patent in our headlines and primetime scoops might as well be the contents of the X-Files any Martian gone astray on earth would contemplate as an interesting subject for an essay on the human condition.

That we are apparently trapped in this vicious cycle worthy of any struggling writer's indignation, that we are running in circles, indicates a failure of imagination. That we appear stuck and trapped in a labyrinth means we have not yet found the way out of the dark. That, indeed, the idea of transcendence and breaking through barriers remain fancy notions devoutly to be wished despite our inventions, our books, our songs.

Failure of imagination is also apparent in the way our leaders and society at large remain in the dark on matters of social renewal and progress that are always the favorite topic of editorials and opinion columns in newspapers and campus publications as well as in socially committed literature. Bad roads, worsening economy, institutional apathy and a sense of drift and despair: these are also metaphors of one simple fact: our limited vision.

How to look at the world in a new light? This continues to be the challenge of every writer, and this is no less of a wrestle than tilting at windmills.

Though World War II, the Holocaust, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki seem like rumors from the past, if not a figment of a nihilistic imagination, this generation can't be deaf to the demonic roar of its own times: the 9/11 tragedy and the horror of a planet plagued by its its inhabitants carelessness and recklessness that flung our world into the pit of imminent extinction.

Against this backdrop oceanic for an existentialist to drown in, our writings might as well be paper boats, a desperate contraption and artificial imitation of Noah's Ark through the deluge of our worries and our nightmares about doomsday scenarios straight from the movie “The Day After Tomorrow.” These cataclysms are really redundant when we reckon that these natural calamities are just variations on a trite theme of “man's fall from grace,” or how this flood of human misery is symptomatic and symbolic of a world damned by a tide of intolerance, enmity, and inequity. Where hatred and hunger, poverty and politicians are facts of life that also hint of the state of our cultural state of being. Where estrangement from our moral moorings and a dislocation of our sensibility are a commonplace.

Failure of imagination is a matter we may ascribe to our politicians and policy-makers. But this is something we delude ourselves or hope to believe we are exempt from as we dare to play God with the purging and transformative power of the written word, out of that cloud in our head we call creative writing.

This is one power worth struggling for even as we try to tame this wild and larger-than-life creature called literature, as we stubbornly attempt to discover meaning in life as well as find life in meaning. That meaning might be found as we conscript ourselves to a crusade for our culture, or when steadfastly and stubbornly assert our identity even if such identity is shadowed by forces more formidable than us and threatens to wipe out our singular voice with which we hope to amplify our authentic experience to which we are umbilically linked.

Failure of imagination happens when the terrible things in the world, conspiring to cast a black eye on humanity, defeats us into seeing it with cold jaded eyes and blinking away the spark of wonder out of our gaze that ought to glint with the “pure wisdom of someone who knows nothing,” as Pablo Neruda would put it. To find something out of nothingness or the void as when another poet, Carolyn Forche, stubbornly exclaims: “Only if the dark conceives it must I think of beauty.”

This knowledge I owe from Neruda and Forche matters most to me about writing beyond theories and shifting schools of thought, beyond history and politics, plot and structure, the literal and the symbolic.

Despite the black wind wafting about, everybody needs metaphors to live by, and everyone has the responsibility (especially writers) to create order or a sense of cosmos out of the chaos of human experience, as much as we strive for a construction of harmony in a poem, or an orderly narrative in a reportage, a novel, a story.

But I agree there is a something much more simple and primitive and elusive that lies at the core of writing that has to do with the mystery of the created world: the need to approach this mystery with fear and loathing, at first, and finally with hope.“Eventually one must put aside the paradoxes and the explanations and simply write,” averred a novelist.

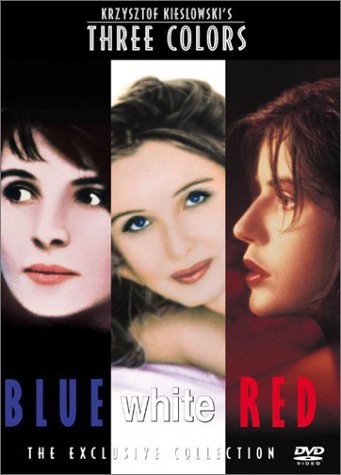

But I agree there is a something much more simple and primitive and elusive that lies at the core of writing that has to do with the mystery of the created world: the need to approach this mystery with fear and loathing, at first, and finally with hope.“Eventually one must put aside the paradoxes and the explanations and simply write,” averred a novelist.Failure of imagination, that's something we can not blame on Cseslaw Milosz who referred to his poems as "bearing witness both to the natural wonders of the earth and the demoniac doings of history in the 20th century." That's something we can not accuse Octavio Paz of, as he devotes himself to the idea that poetic activity is revolutionary in nature, convinced that creative writing is an operation capable of changing the world. Writing, he swears, is both "a means of internal liberation and also a spiritual exercise."

Creative writing, after all, can only be an act of faith, of hoping against hope. That, indeed, something can still be saved. That something left for dead, like our marginalized culture and literature, can still be resurrected.

Though our voices may spawn a howling wilderness of disquiet and questions, it's comforting that there's a coda in the Eucharist that ought to be echoed as the bottomline of our bylines: “We remember. We celebrate. We believe.”

No comments:

Post a Comment