The more blogs change, the more they remain... Still here, but I hope we'd see each other more often there for my latest posts.

The more blogs change, the more they remain... Still here, but I hope we'd see each other more often there for my latest posts.Tuesday, November 25, 2008

This blog has moved to "Run the Rays" (www.brewingmyke.blogspot.com)

The more blogs change, the more they remain... Still here, but I hope we'd see each other more often there for my latest posts.

The more blogs change, the more they remain... Still here, but I hope we'd see each other more often there for my latest posts.Monday, October 27, 2008

From here to there: Leaping into a sleepwalker's runaway romp to a brighter spot

Only thing constant, as the cliche attests, is change. And yet it remains the same, dear visitor, as this site forks into another path en route to a brighter spot. Come on in, see you here.

Thursday, May 15, 2008

Because Lapu-Lapu is neither good only as a fish stew nor a lonely statue

You may take any true-blooded Cebuano out of the ground beneath his feet, but there's no taking away the homebound rhythm of his heartbeat. Wherever he may be, regardless how distant his corner under the sky may be and no matter if his mouth reeks and turns sloppy with the staleness of nostalgia in this age of diaspora, his tongue will always be tattooed with the taste of earth.

Recenly, I created an online hub--a sort of homecoming spot, a melting pot--for creative writers in Cebuano who've been riding the ripples toward the four winds in search of the so-called greener pastures. In strange lands, the ear keens for familiar voices that may be all we will ever need to hear our inner selves in the face of the goblin called globalization, to reclaim and remind ourselves who we were, to begin with, and who we will always be. To go far in the world, all we really need is to stay rooted, no matter the uncertain loam of elsewhere we've chosen to raise our stakes into.

Thus Kabisdak (Kalihokan sa Bisdak nga Katitikan) is born, out loud with something like a battlecry against the cold-blooded spawn of alienation spelled triple in scarlet letters: KKK (kalaay, kalimot, kamingaw). In the face of distance and displacement, may Kabisdak be a way as well for us to touch base with the magsusulat who choose to anchor the flight of imagination in the native shore. Our common ground. Our mainland of memory in the globe-embracing ocean of our saying and singing.

Na hala, dapiton ko kamo ngadto sa balayan sa Kabisdak. Ablihi lang ang ganghaan pinaagi sa pagtuktok-tuplok ning maong luna: www.balaybalakasoy.blogspot.com

Recenly, I created an online hub--a sort of homecoming spot, a melting pot--for creative writers in Cebuano who've been riding the ripples toward the four winds in search of the so-called greener pastures. In strange lands, the ear keens for familiar voices that may be all we will ever need to hear our inner selves in the face of the goblin called globalization, to reclaim and remind ourselves who we were, to begin with, and who we will always be. To go far in the world, all we really need is to stay rooted, no matter the uncertain loam of elsewhere we've chosen to raise our stakes into.

Thus Kabisdak (Kalihokan sa Bisdak nga Katitikan) is born, out loud with something like a battlecry against the cold-blooded spawn of alienation spelled triple in scarlet letters: KKK (kalaay, kalimot, kamingaw). In the face of distance and displacement, may Kabisdak be a way as well for us to touch base with the magsusulat who choose to anchor the flight of imagination in the native shore. Our common ground. Our mainland of memory in the globe-embracing ocean of our saying and singing.

Na hala, dapiton ko kamo ngadto sa balayan sa Kabisdak. Ablihi lang ang ganghaan pinaagi sa pagtuktok-tuplok ning maong luna: www.balaybalakasoy.blogspot.com

Labels:

Cebu,

Cebuano culture,

Poetry,

self-indulgence,

writers

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

candles for china

And then came the end. Too sudden and mind-boggling to comprehend.

And then came the end. Too sudden and mind-boggling to comprehend.To make a long story no shorter than an epitaph, here's the dispatch: "The toll of the dead and missing soared as rescue workers dug through flattened schools and homes on Tuesday in a desperate attempt to find survivors of China's worst earthquake in three decades. The death toll exceeded 12,000 in Sichuan province alone, and 18,645 were still buried in debris in the city of Mianyang, near the epicenter of Monday's massive, 7.9-magnitude quake."

It could happen as well to us, God forbid. What else do we know?

Here's one certainty, according to Ralph Waldo Emerson: "Sorrow makes us all children again, destroys all differences of intellect. The wisest know nothing." God bless all the grief-struck in China. And for the rest of us who, under our fragile place under the bell, can't tell for whom it tolls next.

Saturday, May 10, 2008

ever again, all about her

No contest, us fathers are no match to our kids' mothers. We have no wombs, to begin with, and most of us can only endure the sloppy shape of never-ending pregnancy borne out of all that booze and sloth. No matter if our kids fancy us to be their own Superman, it's often their mothers they run to out of their scraped knees and even when they get circumcised or crazed and dazed about their first monthly period.

Not that I'm complaining. See, I myself confess there's no outgrowing whom I owe the privilege of coming out of her womb. She whose frail frame has absorbed the usual burden, more a matter of choice than necessity every mother worth her milk, birthmark, or wrinkles has become--the stereotype of sacrifice.

My Mama Violeta, veritably nothing out of the ordinary. She who makes any grateful child graceful for simplifying the complicated choreography or stunt of selflessness only because she renders it all--like the lady being sawed inside a magician's box--so easy to see but tough to live up to: tenderness, patience, resilience. (My mother, who finished only grade one, could not read and would only wince at these words, these squiggles of abstractions she steeled me to come to terms with when she inspired me to read, write, read, write as if my life depended on it.)

Hands down, no matter how low we fall, misfortune is not so miserable as long as we have our mothers to call and cry our hearts for when it hurts. Indeed, wretched becomes the world left orphaned or deserted by mothers (or, worse, haunted by the reincarnation of Joan Crawford from Mommie Dearest).

Hands down, no matter how low we fall, misfortune is not so miserable as long as we have our mothers to call and cry our hearts for when it hurts. Indeed, wretched becomes the world left orphaned or deserted by mothers (or, worse, haunted by the reincarnation of Joan Crawford from Mommie Dearest).

How far some mothers go for the sake of their children? Spare me some feminist polemics or further bleeding-heart blather. Consider and see, instead, what Pedro Almodovar shows in his feast of a film, Volver. Yes, there's no magic like mother.

Not that I'm complaining. See, I myself confess there's no outgrowing whom I owe the privilege of coming out of her womb. She whose frail frame has absorbed the usual burden, more a matter of choice than necessity every mother worth her milk, birthmark, or wrinkles has become--the stereotype of sacrifice.

My Mama Violeta, veritably nothing out of the ordinary. She who makes any grateful child graceful for simplifying the complicated choreography or stunt of selflessness only because she renders it all--like the lady being sawed inside a magician's box--so easy to see but tough to live up to: tenderness, patience, resilience. (My mother, who finished only grade one, could not read and would only wince at these words, these squiggles of abstractions she steeled me to come to terms with when she inspired me to read, write, read, write as if my life depended on it.)

Hands down, no matter how low we fall, misfortune is not so miserable as long as we have our mothers to call and cry our hearts for when it hurts. Indeed, wretched becomes the world left orphaned or deserted by mothers (or, worse, haunted by the reincarnation of Joan Crawford from Mommie Dearest).

Hands down, no matter how low we fall, misfortune is not so miserable as long as we have our mothers to call and cry our hearts for when it hurts. Indeed, wretched becomes the world left orphaned or deserted by mothers (or, worse, haunted by the reincarnation of Joan Crawford from Mommie Dearest).How far some mothers go for the sake of their children? Spare me some feminist polemics or further bleeding-heart blather. Consider and see, instead, what Pedro Almodovar shows in his feast of a film, Volver. Yes, there's no magic like mother.

Tuesday, May 06, 2008

Can we hold a candle to the dark wind?

Staggering, the blow of statistics after a cyclone scourged Myanmar. Consider what the locals call an unprecedented nightmare: 22,500 dead so far and 41,000 people still missing.

Last week, death and destruction also mades headlines as tornadoes whirled through the heartland of America. Just another dire reminder of our vulnerability against nature as our ravaged planet alerts us once more with its recurrent distressed call. Are we listening? Doesn't what happened in the Day After Tomorrow ring a bell? If we still think the worst is the stuff of movies only, we're in for some rough reality check.

Last week, death and destruction also mades headlines as tornadoes whirled through the heartland of America. Just another dire reminder of our vulnerability against nature as our ravaged planet alerts us once more with its recurrent distressed call. Are we listening? Doesn't what happened in the Day After Tomorrow ring a bell? If we still think the worst is the stuff of movies only, we're in for some rough reality check.

Hope floats, yes, and may it stay that way a little longer than the glaciers and polar caps in the shiftscape of Antartica.

Happy endings? It's up to us, really. Or so dares another documentary in the wake of An Incovenient Truth. If what's rendered loud and clear in The 11th Hour are any indication, we have more than enough reason to pray what we see isn't what we now get:

Last week, death and destruction also mades headlines as tornadoes whirled through the heartland of America. Just another dire reminder of our vulnerability against nature as our ravaged planet alerts us once more with its recurrent distressed call. Are we listening? Doesn't what happened in the Day After Tomorrow ring a bell? If we still think the worst is the stuff of movies only, we're in for some rough reality check.

Last week, death and destruction also mades headlines as tornadoes whirled through the heartland of America. Just another dire reminder of our vulnerability against nature as our ravaged planet alerts us once more with its recurrent distressed call. Are we listening? Doesn't what happened in the Day After Tomorrow ring a bell? If we still think the worst is the stuff of movies only, we're in for some rough reality check. Hope floats, yes, and may it stay that way a little longer than the glaciers and polar caps in the shiftscape of Antartica.

Happy endings? It's up to us, really. Or so dares another documentary in the wake of An Incovenient Truth. If what's rendered loud and clear in The 11th Hour are any indication, we have more than enough reason to pray what we see isn't what we now get:

Monday, May 05, 2008

Bottoms up, or what's outrageously over the top?

Shit hits the fan when fact proves stranger than fiction. No end to the utterly unthinkable, certainly. Hang on, handy as always is the stunt of suspending disbelief.

About the lower depths some men often descend into, here's a reprint of my regular column, "So To Speak," published in the op-ed pages of Sun.Star Cebu (29 April 2008):

About the lower depths some men often descend into, here's a reprint of my regular column, "So To Speak," published in the op-ed pages of Sun.Star Cebu (29 April 2008):

Loo life

WHO does not give a rat’s ass and wish devoutly to avoid--simply because it does not sit well with us-- a headache on top of a hemorrhoid?

Sweat ourselves shitless. Thus, we do sometimes when confronted, if not confounded, with the manure called human nature. Surreal, how things happen to some people the way they do.

Talk about dumping logic into the loo, and hardly anything can be more utterly absurd than the recent report about a 35-year-old woman in Kansas who got stuck in the lavatory for—hold your breath—two years. So much so that some parts of her butt and the backside of her thighs have leached like second skin to the toilet seat. The police who came to rescue her had to carry “the toilet seat off with a pry bar and the seat went with her to the hospital,” narrated the news.

One of her neighbors, who had not seen her for the last six years, could only shake his head. “I don’t think anybody can make any sense out of it,” he said. But her boyfriend deemed nothing strange. “It just kind of happened one day; she went in and had been in there a little while, the next time it was a little longer.” Tried to coax her out of hiding and fed and bathed and brought her clothes, he did. Or so he claimed “an otherwise normal relationship, except it all happened in the bathroom.”

Vouching for her phobia of being seen in public after she allegedly endured a traumatic childhood, he figured “like it was a safe place for her.”

Ah, the idea of a comfort room. Now that’s stretching the imagination down the sphincter and doesn’t hold even urine or hogwash for those who live in some 18,000 households in Cebu City. They, reportedly, “don’t have access to sanitary toilet facilities and 11,400 others that don’t have access to safe potable water yet.”

Ah, the idea of a comfort room. Now that’s stretching the imagination down the sphincter and doesn’t hold even urine or hogwash for those who live in some 18,000 households in Cebu City. They, reportedly, “don’t have access to sanitary toilet facilities and 11,400 others that don’t have access to safe potable water yet.”

That doesn’t sit pretty for those preening bubbly in the mouth about the beauty of living in the so-called “Queen City of the South.” Fact is stranger than fiction when ordure flies in the face of daydream. No less perplexing than a Sphinx’s riddle for the city mayor who can’t figure out why Cebu—ostensibly one of the “Top 10 Asian Cities of the Future”—ended up a laggard and made it only in the bottom spot in a business magazine’s list of 20 “Best Places to Live” in the country.

Now that’s hardly the stuff of rocket science when the dispatch comes like a kick in the butt of City Hall officials: “Some had to share toilets with their neighbors. In the mountain barangays, some households do with dug-up holes as their makeshift toilet facility, while some still defecate on old newspapers or plastic bags to be thrown away somewhere.” Less bothersome if only Cebu had as much carefree space as the prairies of Kansas, with more than enough breeze to blow away and wipe out the reek of recklessness.

No wonder my nose, now stuffed with allergy against the pollen-filled scent of spring but still runny with a Cebucentric sensibility, gets perennially itchy with infestation of disbelief. The ooze and whiff of outrage. Or shame steeped in intimations of doom. And it’s not only about a woman’s butt wedged too long in the toilet seat, or the YouTube post straight from a surgery room--rowdy with chuckles and celebratory yelps--about a gay man’s rectum jammed with a bottle of perfume.

Sweat ourselves shitless. Thus, we do sometimes when confronted, if not confounded, with the manure called human nature. Surreal, how things happen to some people the way they do.

Talk about dumping logic into the loo, and hardly anything can be more utterly absurd than the recent report about a 35-year-old woman in Kansas who got stuck in the lavatory for—hold your breath—two years. So much so that some parts of her butt and the backside of her thighs have leached like second skin to the toilet seat. The police who came to rescue her had to carry “the toilet seat off with a pry bar and the seat went with her to the hospital,” narrated the news.

One of her neighbors, who had not seen her for the last six years, could only shake his head. “I don’t think anybody can make any sense out of it,” he said. But her boyfriend deemed nothing strange. “It just kind of happened one day; she went in and had been in there a little while, the next time it was a little longer.” Tried to coax her out of hiding and fed and bathed and brought her clothes, he did. Or so he claimed “an otherwise normal relationship, except it all happened in the bathroom.”

Vouching for her phobia of being seen in public after she allegedly endured a traumatic childhood, he figured “like it was a safe place for her.”

Ah, the idea of a comfort room. Now that’s stretching the imagination down the sphincter and doesn’t hold even urine or hogwash for those who live in some 18,000 households in Cebu City. They, reportedly, “don’t have access to sanitary toilet facilities and 11,400 others that don’t have access to safe potable water yet.”

Ah, the idea of a comfort room. Now that’s stretching the imagination down the sphincter and doesn’t hold even urine or hogwash for those who live in some 18,000 households in Cebu City. They, reportedly, “don’t have access to sanitary toilet facilities and 11,400 others that don’t have access to safe potable water yet.”That doesn’t sit pretty for those preening bubbly in the mouth about the beauty of living in the so-called “Queen City of the South.” Fact is stranger than fiction when ordure flies in the face of daydream. No less perplexing than a Sphinx’s riddle for the city mayor who can’t figure out why Cebu—ostensibly one of the “Top 10 Asian Cities of the Future”—ended up a laggard and made it only in the bottom spot in a business magazine’s list of 20 “Best Places to Live” in the country.

Now that’s hardly the stuff of rocket science when the dispatch comes like a kick in the butt of City Hall officials: “Some had to share toilets with their neighbors. In the mountain barangays, some households do with dug-up holes as their makeshift toilet facility, while some still defecate on old newspapers or plastic bags to be thrown away somewhere.” Less bothersome if only Cebu had as much carefree space as the prairies of Kansas, with more than enough breeze to blow away and wipe out the reek of recklessness.

No wonder my nose, now stuffed with allergy against the pollen-filled scent of spring but still runny with a Cebucentric sensibility, gets perennially itchy with infestation of disbelief. The ooze and whiff of outrage. Or shame steeped in intimations of doom. And it’s not only about a woman’s butt wedged too long in the toilet seat, or the YouTube post straight from a surgery room--rowdy with chuckles and celebratory yelps--about a gay man’s rectum jammed with a bottle of perfume.

Wednesday, April 30, 2008

Let there be library

Where on earth do angels delight to hang out? Not inside cathedrals, no! As shown in my most cherished film, Wings of Desire, nowhere else are angels nearer to heaven than under the roof of a library. How they tarry and eavesdrop where silence hums in chorus with the constellation of words between the covers, hovering around readers.

Where on earth do angels delight to hang out? Not inside cathedrals, no! As shown in my most cherished film, Wings of Desire, nowhere else are angels nearer to heaven than under the roof of a library. How they tarry and eavesdrop where silence hums in chorus with the constellation of words between the covers, hovering around readers.With the recent celebration of the National Library Week (April 13-19, 2008), here's a curtsy to retired Maine librarian Glenna Nowell as she piques public curiosity on books.

Since 1988, Nowell has been writing to celebrities (presidents, actors, athletes and a couple of United Nations secretaries general) to ask and take note of their favorite page-turners. “I was looking for a hook that would get people to read a book,” explains Nowell, who wishes to steer literate folks toward stuffs beyond the bestsellers.

Check out Nowell’s Celebrity Reading List over the years and take your cue on “Who Reads What?”

~~~ * ~~~

"Some books are to be tasted, others swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested.”

"Some books are to be tasted, others swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested.”True to the words of Sir Francis Bacon, 27 culinary bibliophiles in Topeka, Kansas recently whipped up their imagination as sweetly as literally possible. The cake of their creativity took the spotlight at the reception and exhibit of the annual Edible Books Festival last April 4th at the Topeka and Shawnee County Public Library. Up for grabs were prizes for Best in Show, Most Book-Like, and Most Likely To Be Devoured that were chosen by votes from the exhibit’s audience.

While my kids tarried longer in front of the “Cat in the Hat” and “Snowballs” cakes, I slurped over the gothic confection patterned after Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart.”

For more pictures of the entries and the winning edible books, check out the photo album in the library’s website.

Who in the world are we?

We're all alone, avers a song. But now that connectivity is just at the tip of our fingertips in this Age of the Internet, isolation takes a common and ironic turn.

We're all alone, avers a song. But now that connectivity is just at the tip of our fingertips in this Age of the Internet, isolation takes a common and ironic turn.Along that line goes the gist of one of my recent columns "So To Speak" in the op-ed page of Sun.Star Cebu (April 24, 2008). Hereunder is the reprint:

Sharing our story

BLOOD boiled up to their eyes. Upset by the ugly comments about them in their classmate's blog, eight high school students in Florida are now facing charges after they reportedly battered the poor young lady and left her almost unrecognizable.

Such blind rage, indeed, after they felt belittled in her MySpace page. What an oversight for her as well to have raised an eyebrow, looking for trouble by seeing other people in a bad light. In the netherworld of “nada” where one is degraded or rendered insignificant, invisible.

Who wants to be written off into the ignominy of anonymity? Not those who admitted to have Googled themselves at some point in their lives. They comprise almost half of the respondents (47 percent) in a recent survey by the Pew Internet and American Life Project that aims "to produce reports that explore the impact of the Internet on families, communities, work and home, daily life, education, health care, and civic and political life."

One's sense of self, in this age of Net surfing, can either sink or stay above water. "I Google myself to see what kinds of waves my life is making in the world," affirms travel writer Frank Bures in the latest edition of Poets and Writers Magazine. "Isn't that why writers, artists, and other egomaniacs obsess over the Amazon ranking of their book, the comments on their blogs, the hits on their websites?"

Almost desperate, what seems an emergency to make our presences felt—upending our universal isolation---in the grand scheme of technology. In this digital world, the democracy of bloggers and YouTube uploaders means never having to say sorry. Particularly in a pell-mell attempts at autobiography, a puny and slapdash binge at shaping some moments—no matter how trivial, or utterly devoid of larger-than-life hallmarks of heroism—against the flux called history.

Almost desperate, what seems an emergency to make our presences felt—upending our universal isolation---in the grand scheme of technology. In this digital world, the democracy of bloggers and YouTube uploaders means never having to say sorry. Particularly in a pell-mell attempts at autobiography, a puny and slapdash binge at shaping some moments—no matter how trivial, or utterly devoid of larger-than-life hallmarks of heroism—against the flux called history.

Never mind if one can't cast one's words in gold with the touch of a Resil Mojares, who laments the lack of memoirs and autobiographies. "Since people do not leave behind written accounts of their lives, we miss out on a lot of the personal, human details of how larger histories are made," explains Mojares at the book launching of "Shapes of Memory," the biography of Cebuano labor leader and trade unionist Democrito T. Mendoza.

Sweat the small stuff, baby. "Little things can lead you to big events…," attests Mendoza, explaining the necessity "to write the details of his life…to encourage young people to face challenges and be ready to risk everything to achieve a better life." For a broad base of contacts, Mendoza might try to open a Multiply account.

Uploading himself at YouTube for a wider audience of his inspiring tale, however, might be a strain for him. He won't stand a chance, no matter how noble he is, compared to the almost extra-terrestrial dimensions of human condition shown in the unlimited scope of its videos.

It's where one can spot, for instance, a perfume canister stuck into someone's rectum. And how the victim ends up literally the butt of jokes, sprawled in the surgery room as the cameras zoom into the twilight zone of his anatomy. Behold the sharp edges of laughter cutting him to pieces, piercing us who witness into complicity. So much for a shared story.

Such blind rage, indeed, after they felt belittled in her MySpace page. What an oversight for her as well to have raised an eyebrow, looking for trouble by seeing other people in a bad light. In the netherworld of “nada” where one is degraded or rendered insignificant, invisible.

Who wants to be written off into the ignominy of anonymity? Not those who admitted to have Googled themselves at some point in their lives. They comprise almost half of the respondents (47 percent) in a recent survey by the Pew Internet and American Life Project that aims "to produce reports that explore the impact of the Internet on families, communities, work and home, daily life, education, health care, and civic and political life."

One's sense of self, in this age of Net surfing, can either sink or stay above water. "I Google myself to see what kinds of waves my life is making in the world," affirms travel writer Frank Bures in the latest edition of Poets and Writers Magazine. "Isn't that why writers, artists, and other egomaniacs obsess over the Amazon ranking of their book, the comments on their blogs, the hits on their websites?"

Almost desperate, what seems an emergency to make our presences felt—upending our universal isolation---in the grand scheme of technology. In this digital world, the democracy of bloggers and YouTube uploaders means never having to say sorry. Particularly in a pell-mell attempts at autobiography, a puny and slapdash binge at shaping some moments—no matter how trivial, or utterly devoid of larger-than-life hallmarks of heroism—against the flux called history.

Almost desperate, what seems an emergency to make our presences felt—upending our universal isolation---in the grand scheme of technology. In this digital world, the democracy of bloggers and YouTube uploaders means never having to say sorry. Particularly in a pell-mell attempts at autobiography, a puny and slapdash binge at shaping some moments—no matter how trivial, or utterly devoid of larger-than-life hallmarks of heroism—against the flux called history.Never mind if one can't cast one's words in gold with the touch of a Resil Mojares, who laments the lack of memoirs and autobiographies. "Since people do not leave behind written accounts of their lives, we miss out on a lot of the personal, human details of how larger histories are made," explains Mojares at the book launching of "Shapes of Memory," the biography of Cebuano labor leader and trade unionist Democrito T. Mendoza.

Sweat the small stuff, baby. "Little things can lead you to big events…," attests Mendoza, explaining the necessity "to write the details of his life…to encourage young people to face challenges and be ready to risk everything to achieve a better life." For a broad base of contacts, Mendoza might try to open a Multiply account.

Uploading himself at YouTube for a wider audience of his inspiring tale, however, might be a strain for him. He won't stand a chance, no matter how noble he is, compared to the almost extra-terrestrial dimensions of human condition shown in the unlimited scope of its videos.

It's where one can spot, for instance, a perfume canister stuck into someone's rectum. And how the victim ends up literally the butt of jokes, sprawled in the surgery room as the cameras zoom into the twilight zone of his anatomy. Behold the sharp edges of laughter cutting him to pieces, piercing us who witness into complicity. So much for a shared story.

Labels:

blogging,

self-indulgence,

Sun.Star opinion column

Saturday, April 26, 2008

Give us this day our daily verse

Reality bites for those rabid about reading. The news, particulary. The stuff of headlines, the wounds we have to lick, the bloodhound smell of fear and loathing--all the stomach-churning facts never go prosaic.

Reality bites for those rabid about reading. The news, particulary. The stuff of headlines, the wounds we have to lick, the bloodhound smell of fear and loathing--all the stomach-churning facts never go prosaic.How to deal with a deeper hunger? The French poet Charles Baudelaire replies, tongue in cheek: "Any healthy man can go without food for two days--but not without poetry."

For those in dire need of words as soul food, so to speak, watch and listen to this video inspired by the poem titled "Eating Poetry" by Pulitzer Prize winner Mark Strand:

Friday, April 25, 2008

Past food

Unappetizing, what's often up in the air lately. Even the so-called land of plenty is getting jittery, with two major American bulk retailers--Sam's Club and Costco--reportedly "rationing the sale of large bags of rice to consumers amid a growing global food crisis marked by skyrocketing prices and heavy pressure on demand. "

Unappetizing, what's often up in the air lately. Even the so-called land of plenty is getting jittery, with two major American bulk retailers--Sam's Club and Costco--reportedly "rationing the sale of large bags of rice to consumers amid a growing global food crisis marked by skyrocketing prices and heavy pressure on demand. "Last week, Sam's Club--a chain owned by retail giant Wal-Mart-- announced a "temporary cap," placing a limit of four 20-pound (nine-kilogram) bags per person for imported jasmine, basmati and long grain white rices as a "precautionary step."

If America is bracing for some belt-tightening measure, imagine how some people elsewhere in the world are putting up with an empty stomach. As a Cebuano phrase puts it, "pasmo hasta bitok."

Hereunder is a reprint of one of my recent column "So To Speak" in the op-ed page of Sun.Star Cebu (April 15, 2008):

Wish Upon the Starved

WHEREVER poverty prevails, America is a finger-licking fantasy. Thus out on their limbs go the dreamers in droves—and not a few would go as far as to swallow swords—to have their fill of the “land of milk and honey.”

That sounds like the end of a bedtime story, true. Especially when it goes against the grain of current events where rice, or the lack of it, has become grist for the mill.

Toss restless in the dark as empty innards turn. So goes the rabble roused by the nightmare in Haiti, where the prime minister got himself booted out to appease a famished populace protesting against soaring prices of food.

Toss restless in the dark as empty innards turn. So goes the rabble roused by the nightmare in Haiti, where the prime minister got himself booted out to appease a famished populace protesting against soaring prices of food.

Mouthfuls of rage also echo in Egypt and Bangladesh where dissent have turned deadly over the same intestinal issue. A worldwide trend, explain the experts who see “a widening gulf between those who can afford to eat and those who cannot.” It looms over much of the world’s population now reeling under the specter of climate change and escalating fuel prices, according to the United Nations.

Simply one plus one—how the transport of food all over the world entails diesel, driving its cost up the stratosphere. Not hard to digest why not only rats are bracing to end up in the sewer, with their bellies up.

In the Philippines and other Asian nations, superstition abounds about the deadly outcome of sleeping with a full stomach. Tongues wag hairy about a nocturnal malady allegedly caused by carbohydrates in rice—the common staple in our table—that mysteriously transmogrify into a “batibat.” An overweight witch-like creature in Ilocano folklore, the “batibat” would supposedly immobilize and suffocate the sleeping victim—mostly male—by squatting on his face.

Clear as day, what we call “bangungot” or “urom” has become too real as the rice crisis haunts the country. Will the protest-plagued leadership weather another thumb-biting spell of insecurity?

To spare the people from the “gut-wrenching pain of hunger under these very difficult times,” Cebu City Councilor Edgardo Labella has proposed “a resolution for the creation of an anti-hunger task force to expedite the implementation of the government’s hunger mitigation programs.”

But where the rule of law is often sidetracked, how far will state initiatives to distribute crop goods to urban areas and metropolis go?

Here in America, now in the throes of an economic recession, there’s also a lot to bellyache against the domino effect vis-à-vis the escalating costs of energy, housing, health insurance and grocery items. According to the US Department of Agriculture, 38 million Americans—13.9 million of them children—live in households at risk of hunger.

Look how it renders the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC), a national nonprofit organization, in full steam “to improve public policies and community partnerships to eradicate hunger and undernutrition in the United States.” On behalf of those who need help to stave off starvation—the elderly, the unemployed, low-income workers, the ill, and the homeless—FRAC has been providing information to strengthen federal nutrition programs, like the distribution of food stamps.

Look how it renders the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC), a national nonprofit organization, in full steam “to improve public policies and community partnerships to eradicate hunger and undernutrition in the United States.” On behalf of those who need help to stave off starvation—the elderly, the unemployed, low-income workers, the ill, and the homeless—FRAC has been providing information to strengthen federal nutrition programs, like the distribution of food stamps.

And so, if it’s any consolation to those yearning to flee from Third World reality, often deemed doggone, hunger is also a persistent stalker here in dreamland.

That sounds like the end of a bedtime story, true. Especially when it goes against the grain of current events where rice, or the lack of it, has become grist for the mill.

Toss restless in the dark as empty innards turn. So goes the rabble roused by the nightmare in Haiti, where the prime minister got himself booted out to appease a famished populace protesting against soaring prices of food.

Toss restless in the dark as empty innards turn. So goes the rabble roused by the nightmare in Haiti, where the prime minister got himself booted out to appease a famished populace protesting against soaring prices of food.Mouthfuls of rage also echo in Egypt and Bangladesh where dissent have turned deadly over the same intestinal issue. A worldwide trend, explain the experts who see “a widening gulf between those who can afford to eat and those who cannot.” It looms over much of the world’s population now reeling under the specter of climate change and escalating fuel prices, according to the United Nations.

Simply one plus one—how the transport of food all over the world entails diesel, driving its cost up the stratosphere. Not hard to digest why not only rats are bracing to end up in the sewer, with their bellies up.

In the Philippines and other Asian nations, superstition abounds about the deadly outcome of sleeping with a full stomach. Tongues wag hairy about a nocturnal malady allegedly caused by carbohydrates in rice—the common staple in our table—that mysteriously transmogrify into a “batibat.” An overweight witch-like creature in Ilocano folklore, the “batibat” would supposedly immobilize and suffocate the sleeping victim—mostly male—by squatting on his face.

Clear as day, what we call “bangungot” or “urom” has become too real as the rice crisis haunts the country. Will the protest-plagued leadership weather another thumb-biting spell of insecurity?

To spare the people from the “gut-wrenching pain of hunger under these very difficult times,” Cebu City Councilor Edgardo Labella has proposed “a resolution for the creation of an anti-hunger task force to expedite the implementation of the government’s hunger mitigation programs.”

But where the rule of law is often sidetracked, how far will state initiatives to distribute crop goods to urban areas and metropolis go?

Here in America, now in the throes of an economic recession, there’s also a lot to bellyache against the domino effect vis-à-vis the escalating costs of energy, housing, health insurance and grocery items. According to the US Department of Agriculture, 38 million Americans—13.9 million of them children—live in households at risk of hunger.

Look how it renders the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC), a national nonprofit organization, in full steam “to improve public policies and community partnerships to eradicate hunger and undernutrition in the United States.” On behalf of those who need help to stave off starvation—the elderly, the unemployed, low-income workers, the ill, and the homeless—FRAC has been providing information to strengthen federal nutrition programs, like the distribution of food stamps.

Look how it renders the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC), a national nonprofit organization, in full steam “to improve public policies and community partnerships to eradicate hunger and undernutrition in the United States.” On behalf of those who need help to stave off starvation—the elderly, the unemployed, low-income workers, the ill, and the homeless—FRAC has been providing information to strengthen federal nutrition programs, like the distribution of food stamps.And so, if it’s any consolation to those yearning to flee from Third World reality, often deemed doggone, hunger is also a persistent stalker here in dreamland.

Thursday, April 17, 2008

Six years of the rest of our days

THERE'S NO perfect marriage, true. Sex is not always sensational. The piles on the kitchen sink and the trash can often lay more precarious and shudder faster than the tectonic shifts of one's patience. The wedding ring might as well grow fungi around one's dirty finger. Et cetera, et cetera.

THERE'S NO perfect marriage, true. Sex is not always sensational. The piles on the kitchen sink and the trash can often lay more precarious and shudder faster than the tectonic shifts of one's patience. The wedding ring might as well grow fungi around one's dirty finger. Et cetera, et cetera. Then again, there's also no adventure more awesome than this: A man and a woman daring to commit themselves into a leap of faith smack into the tightrope of a balancing act, transcending their differences across the uni(que)verse of their individuality. Or through the uncertain spaces--at the edge of solitude--where two people decide contra mundum to belong to no one else other than the separate spheres of each other's evolving selves.

Theologists say we can never be at home until we become one with our God. But finding bliss, a spot under the sun of Divine Providence, is possible in the company we keep because they come to us like a cherished answer to a prayer. Like my Arlaine: wife (nagger, usahay :), mother of my children, lover, friend, conspirator and witness to the weather of my ever-changing sense of becoming a better version of myself each day.

Today, in our 6th anniversary as man and wife, I can only gaze at the uncertainty of the future and whatever it takes heaven may come our way with the gratitude and hope of an open heart.

For the time being, allow me to hum "Amen" to Luther Vandross as he sings a hymn for "All The Woman I Need." Thank you, dearest Wawa.

Friday, April 11, 2008

Forked tongues and the lip-smacking Cebuano language

ON THE MATTER of my mother tongue, there's no ifs and buts. Either I wag it with the earnestness of the dispossesed rabid against the insidious infestation of forgetting, a betrayal against my birthright. Or, be struck mute by the blinding flash and haze of a colonized consciousness.

ON THE MATTER of my mother tongue, there's no ifs and buts. Either I wag it with the earnestness of the dispossesed rabid against the insidious infestation of forgetting, a betrayal against my birthright. Or, be struck mute by the blinding flash and haze of a colonized consciousness.That I also write in English is no less a privilege, yes. Yet it also cast upon this Bisdak dog the added burden of responsibity to be steadfast with the umbilical words of a vernacular on the verge of extinction. Unrelenting, after all, are the inroads of globalization and an unenlightened state policy that spawns negligence, niggardly attention and a culturally decentered outlook of this generation of native speakers.

Pastilan intawon, pagka-serious! Maybe because Yoyoy Villame is dead, and Max Surban is no longer as loud as the cat in heat on the roof.

Hereunder are variations on the Bisdak theme I wrote for my regular column, "So To Speak," in the op-ed pages of Sun.Star Cebu:

La Vida Local and Being Vocal

/Sun.Star Cebu, 8 April 2008/

KIDS say the darndest thing, concedes an eponymous American television series several years ago. But what comes out of the mouths of babes does not always disarm adults with amusement. Bile drips and foams as well from their milk-smacking lips.

Look, for instance, at a clique of child rockers called the Naked Brothers Band. It might as well be a bomb's detonation, what they revealed at the recent 2008 Kids' Choice Awards over the cable channel Nickelodeon. Simply piercing like shrapnel in bare skin, the lyrics of their latest hit: "And I'm really tired of being treated/ Like a fool./ I don't want to go to school…You always tell me to stop/ To stop comin' around/ I can't even make/Make make no sound…."

That struck a cringe-worthy chord, indeed, with the alleged conspiracy of third-grade classmates out "to harm or kill their teacher with a serrated steak knife." Nine pupils at Carter Elementary School in Georgia could be facing "unruly child" charges after they reportedly plotted revenge against their teacher who disciplined a girl for "standing on a chair." Did she say something that reeked of impudence, the tactless assertion of innocence?

As a parent, whittling down the tongues of my two boys into timidity would be no better than bearing my neck down the chopboard. Mince no words, and mean it with due respect. Like, well, saying I look like a hobgoblin and hugging me anyway.

As a parent, whittling down the tongues of my two boys into timidity would be no better than bearing my neck down the chopboard. Mince no words, and mean it with due respect. Like, well, saying I look like a hobgoblin and hugging me anyway.May they grow up to be outspoken but neither intimidating nor insincere. And, yes, to stay true and rooted—even if their vocabulary branches out to the lush forest of other languages—to their mother tongue.

So far, it warms the cockles inside my chest to hear my eldest son Gabriel Ollivan, a minority among his white classmates in preschool, asking ardently, "Unsa'y Binisaya…?" for some things he absorbs from his teacher and his books utterly awash with information and expressions of all things American. Rest assured I do as well when Golli's younger brother Raphael Gandalf, scared of "agta" and "ungo" lurking in the thicket of his two-year-old imagination, easily takes comfort with a bedtime browsing of Mother Goose rhymes no more than the lull of lisping into a medley of native memory about, among others, the "alimango sa suba, gibantog nga dili makuha" and "balay ko sa langit nagasidlak-sidlak luyo sa panganod…." Or the wisdom of "bugsay, bugsay, kiling-kiling dyutay...sa barotong gamay."

Rock and bring it on, Bisdak! Thus I have only the best wishes for the brainchild of Cebu Provincial Board (PB) member Victor Maambong who recently sponsored a resolution for the Department of Education to prescribe "Sugbuanong Binisaya as the indispensable bridge language in teaching English and Filipino" in grade and high schools.

Noting the dismal results of the national achievement tests and taking the cue of scientific studies, Maambong's resolution avers: "The use of the first language to bridge English and Filipino will facilitate a more efficient cognitive process in the language development of our students…," who, certainly, will find it easier to sway along the tune of Naked Brothers Band's "I Don't Want To Go To School," if they fall in the gap or in the shadow between the idea and the act.

Getting a failing grade deserves better, indeed, than the silence of the dumb. Or the stench of cliché while invoking, "Shit," if not the four-letter word. As a matter of fact, they can be more emphatic by exclaiming, "Hinampak!"

Watch Your Mouth

/Sun.Star Cebu, 12 February 2008/

"HE SAID a bad word." So went the accusation of a little Fil-Am boy whose twang-laced tongue has been irradiated with a smattering of Cebuano words from his constant exposure at playtime with my five-year-old son. "He called me stupid, mom."

Even if there are times I won't begrudge "stupid" as an apt adjective for me, my wife can swear we never use that word at home, although I'm fond of ejaculating, "Bulay-og baya!," if anything went out of whack. Now, where did my son get the word that whipped his friend into such distress? My disconsolate wife and I learned later that the infestation in my son's vocabulary was the latest he cottoned onto from his American classmates in pre-kindergarten.

Even if there are times I won't begrudge "stupid" as an apt adjective for me, my wife can swear we never use that word at home, although I'm fond of ejaculating, "Bulay-og baya!," if anything went out of whack. Now, where did my son get the word that whipped his friend into such distress? My disconsolate wife and I learned later that the infestation in my son's vocabulary was the latest he cottoned onto from his American classmates in pre-kindergarten.But what alarmed me, more than the likelihood that I might have spawned a ruffian who would grow up calling a spade a blunt spade, was that he didn't call his friend "amaw." Or, if he were a sharper chip off his old block, he could have stumped even Dennis the Menace with this snarl: "Hungog!"

What other homegrown words, even the hair-raising ones, would soon be watered down into the milk and honey of American speech?

When we flew into the heartland of America nearly a year ago, our baggage bristled with a stack utterly Bisdak—a Cebuano bible, a Jesuit-authored English-Visayan dictionary, booklets from the Cebuano Studies Center featuring a trove of riddles, proverbs, folktales and native songs as well as a slew of CDs (the discography of Yoyoy Villame and Max Surban, three volumes of Visayan Greatest Hits by various artists, Susan Fuentes' "Awitnong Bahandi" album and "Sine-sine" by Missing Filemon.) These, I hoped, would suffice to slam the intrusive clangor of dislocation out the door.

But the new culture, with all its colors bleaching into the televised cartoons, has been unrelenting in weaning my two kids away from their mother tongue. Even if my wife and I have made it sacrosanct for our relocated household to be steeped in the stew of our vernacular, not a day passes without my youngest son blurting out, "No way!"

Out loud, such obstinacy echoes how I feel about one Cebuano lawmaker whose brainchild in Congress now braces like a bulldozer against the dwindling wilderness of indigenous languages. If Rep. Eduardo R. Gullas (Cebu, 1st district) will have his way with House Bill 305—set to revive English as the mandatory language for teaching in all school levels—superseded becomes the Department of Education order implementing the bilingual teaching policy. Which has stunted the potentials of students to compete in the global economy, according to Gullas. His bill would correct the defects of the current education program where "learning two languages (English and Pilipino) is too much for young Filipino learners, especially the non-Tagalog speaking children." But don't impressionable minds work like a sponge? Or, to begin with, must the bilingual system be thrown with the bathwater because it has been childishly conceived and carried out by a way of teaching slightly better than baby-talk?

If the national language — predominantly Tagalog — languishes, where does that leave the rest of the regional languages? Must progress be paid by selling what little remains of oral heritage down the river?

If the national language — predominantly Tagalog — languishes, where does that leave the rest of the regional languages? Must progress be paid by selling what little remains of oral heritage down the river?First things first, suggests a study recently printed in the Jakarta Post: "Students learn English or acquire a second language more rapidly and effectively if they maintain and develop their proficiency in their mother tongue." Swords, no more than the tongue's artillery of words, are better if they are double-edged.

Next time my son said "stupid" I would know for whom it's best suited. And I swear to add an expletive, crispier in Cebuano, for a deadlier effect.

An earful of angels

Feeling small and separate? Here's a soothing reminder from "Far Away," one of the uplifting songs of the children's choir Libera: "...Whenever I cry/ Far away and anywhere./ You hear me call when shadows fall/ your light of hope showing me the way."

Wednesday, April 02, 2008

Ode to the ordinary, an epic of simplicity

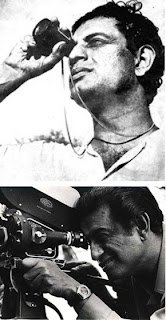

The Radiance of Satyajit Ray's 'The Apu Trilogy'

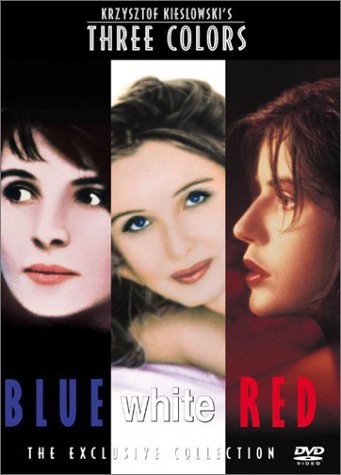

THREE is a mystical number, and cinephiles would concur thrice about the best in cinematic history. Francis Ford Copolla's The Godfather series. Krzysztof Kieslowski's poetic reverie on White, Blue, and Red. Peter Jackson's monumental Lord of the Rings saga. All have thunder and lightning all over them, the lush light of grand design, the flourish of an operatic aria.

THREE is a mystical number, and cinephiles would concur thrice about the best in cinematic history. Francis Ford Copolla's The Godfather series. Krzysztof Kieslowski's poetic reverie on White, Blue, and Red. Peter Jackson's monumental Lord of the Rings saga. All have thunder and lightning all over them, the lush light of grand design, the flourish of an operatic aria.

Imagine, therefore, how orgasmic I felt when I got hold of the trilogy's DVD set recently. With almost masturbatory focus, I filled April Fool's Day with a complete viewing of it in one setting.

Imagine, therefore, how orgasmic I felt when I got hold of the trilogy's DVD set recently. With almost masturbatory focus, I filled April Fool's Day with a complete viewing of it in one setting.

Ray (1921-1992) was a commercial artist in Calcutta with little money and no connections when he determined to adapt a famous serial novel about the birth and young manhood of Apu--born in a rural village, formed in the holy city of Benares, educated in Calcutta, then a wanderer. The legend of the first film is inspiring; how on the first day Ray had never directed a scene, his cameraman had never photographed one, his child actors had not even been tested for their roles--and how that early footage was so impressive it won the meager financing for the rest of the film. Even the music was by a novice, Ravi Shankar, later to be famous.

Ray (1921-1992) was a commercial artist in Calcutta with little money and no connections when he determined to adapt a famous serial novel about the birth and young manhood of Apu--born in a rural village, formed in the holy city of Benares, educated in Calcutta, then a wanderer. The legend of the first film is inspiring; how on the first day Ray had never directed a scene, his cameraman had never photographed one, his child actors had not even been tested for their roles--and how that early footage was so impressive it won the meager financing for the rest of the film. Even the music was by a novice, Ravi Shankar, later to be famous.

The trilogy begins with "Pather Panchali," filmed between 1950 and 1954. Here begins the story of Apu when he is a boy, living with his parents, older sister and ancient aunt in the ancestral village to which his father, a priest, has returned despite the misgivings of the practical mother. The second film, "Aparajito" (1956), follows the family to Benares, where the father makes a living from pilgrims who have come to bathe in the holy Ganges. The third film, "The World of Apu" (1959), finds Apu and his mother living with an uncle in the country; the boy does so well in school he wins a scholarship to Calcutta. He is married under extraordinary circumstances, is happy with his young bride, then crushed by the deaths of his mother and his wife. After a period of bitter drifting, he returns at last to take up the responsibility of his son.

This summary scarcely reflects the beauty and mystery of the films, which do not follow the punched-up methods of conventional biography but are told in the spirit of the English title of the first film, "The Song of the Road." The actors who play Apu at various ages from about 6 to 29 have in common a moody, dreamy quality; Apu is not sharp, hard or cynical, but a sincere, naive idealist, motivated more by vague yearnings than concrete plans. He reflects a society that does not place ambition above all, but is philosophical, accepting, optimistic.

This summary scarcely reflects the beauty and mystery of the films, which do not follow the punched-up methods of conventional biography but are told in the spirit of the English title of the first film, "The Song of the Road." The actors who play Apu at various ages from about 6 to 29 have in common a moody, dreamy quality; Apu is not sharp, hard or cynical, but a sincere, naive idealist, motivated more by vague yearnings than concrete plans. He reflects a society that does not place ambition above all, but is philosophical, accepting, optimistic.

Sharmila Tagore, who plays Aparna, was only 14 when she made the film. She projects exquisite shyness and tenderness, and we consider how odd it is to be suddenly married to a stranger. "Can you accept a life of poverty?" asks Apu, who lives in a single room and augments his scholarship with a few rupees earned in a print shop. "Yes," she says simply, not meeting his gaze. She cries when she first arrives in Calcutta, but soon sweetness and love shine out through her eyes. Soumitra Chatterjee, who plays Apu, shares her innocent delight, and when she dies in childbirth it is the end of his innocence and, for a long time, of his hope.

Sharmila Tagore, who plays Aparna, was only 14 when she made the film. She projects exquisite shyness and tenderness, and we consider how odd it is to be suddenly married to a stranger. "Can you accept a life of poverty?" asks Apu, who lives in a single room and augments his scholarship with a few rupees earned in a print shop. "Yes," she says simply, not meeting his gaze. She cries when she first arrives in Calcutta, but soon sweetness and love shine out through her eyes. Soumitra Chatterjee, who plays Apu, shares her innocent delight, and when she dies in childbirth it is the end of his innocence and, for a long time, of his hope.

The actors in the films have all been cast from life, to type; Italian neorealism was in vogue in the early 1950s, and Ray would have heard and agreed with the theory that everyone can play one role--himself. The most extraordinary performer in the films is Chunibala Devi, who plays the old aunt, stooped double, deeply wrinkled. She was 80 when shooting began; she had been an actress decades ago, but when Ray sought her out, she was living in a brothel, and thought he had come looking for a girl. When Apu's mother angers at her and tells her to leave, notice the way she appears at the door of another relative, asking, "Can I stay?" She has no home, no possessions except for her clothes and a bowl, but she never seems desperate because she embodies complete acceptance.

THREE is a mystical number, and cinephiles would concur thrice about the best in cinematic history. Francis Ford Copolla's The Godfather series. Krzysztof Kieslowski's poetic reverie on White, Blue, and Red. Peter Jackson's monumental Lord of the Rings saga. All have thunder and lightning all over them, the lush light of grand design, the flourish of an operatic aria.

THREE is a mystical number, and cinephiles would concur thrice about the best in cinematic history. Francis Ford Copolla's The Godfather series. Krzysztof Kieslowski's poetic reverie on White, Blue, and Red. Peter Jackson's monumental Lord of the Rings saga. All have thunder and lightning all over them, the lush light of grand design, the flourish of an operatic aria. And then there's Satyajit Ray's The Apu Trilogy. Unerring, almost God-like, the way it weaves a spell of beauty through scenes illumined with the randomly familiar, catching the world of its characters in the spider-web rhythms of the ordinary. No larger-than-life gestures here. No highlights of blinding virtuosity. No soaring musical score other than the simple but haunting strain of Ravi Shankar's sitar.

But listen how the great Akira Kurosawa raved: "Not to have seen the cinema of Satyajit Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon... It is the kind of cinema that flows with the serenity and nobility of a big river."

And so, taking Kurosawa's cue, it was with nearly erotic abandon that I went to the screening of Ray's The Apu Trilogy during a retrospective film festival at SM City Cebu several years ago.

Seduced by Ray's evocative rendition of a poor family's life in a small Bengali village in Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road) and their migration to the holy city of Benares in Aparajito (The Unvanquished), imagine nothing less than coitus interruptus when the projector conked out unceremoniously on Apu Sansar (The World of Apu), the trilogy's last installment.

Imagine, therefore, how orgasmic I felt when I got hold of the trilogy's DVD set recently. With almost masturbatory focus, I filled April Fool's Day with a complete viewing of it in one setting.

Imagine, therefore, how orgasmic I felt when I got hold of the trilogy's DVD set recently. With almost masturbatory focus, I filled April Fool's Day with a complete viewing of it in one setting. Truly, the trilogy more than holds a candle to Orson Welles' Citizen Kane as one of the most promethean debuts in the annals of filmmaking. Nothing less than miraculous, indeed, how Ray edifies everyday life in each of the three films, "refusing to divorce beauty from tragedy, rendering the ordinary majestic and discovering insight and ironies in the smallest of moments."

Hereunder is a review from Roger Ebert (the first film critic to win the Pulitzer Prize):

THE great, sad, gentle sweep of "The Apu Trilogy" remains in the mind of the moviegoer as a promise of what film can be. Standing above fashion, it creates a world so convincing that it becomes, for a time, another life we might have lived. The three films, which were made in India by Satyajit Ray between 1950 and 1959, swept the top prizes at Cannes, Venice and London, and created a new cinema for India--whose prolific film industry had traditionally stayed within the narrow confines of swashbuckling musical romances. Never before had one man had such a decisive impact on the films of his culture.

Ray (1921-1992) was a commercial artist in Calcutta with little money and no connections when he determined to adapt a famous serial novel about the birth and young manhood of Apu--born in a rural village, formed in the holy city of Benares, educated in Calcutta, then a wanderer. The legend of the first film is inspiring; how on the first day Ray had never directed a scene, his cameraman had never photographed one, his child actors had not even been tested for their roles--and how that early footage was so impressive it won the meager financing for the rest of the film. Even the music was by a novice, Ravi Shankar, later to be famous.

Ray (1921-1992) was a commercial artist in Calcutta with little money and no connections when he determined to adapt a famous serial novel about the birth and young manhood of Apu--born in a rural village, formed in the holy city of Benares, educated in Calcutta, then a wanderer. The legend of the first film is inspiring; how on the first day Ray had never directed a scene, his cameraman had never photographed one, his child actors had not even been tested for their roles--and how that early footage was so impressive it won the meager financing for the rest of the film. Even the music was by a novice, Ravi Shankar, later to be famous. The trilogy begins with "Pather Panchali," filmed between 1950 and 1954. Here begins the story of Apu when he is a boy, living with his parents, older sister and ancient aunt in the ancestral village to which his father, a priest, has returned despite the misgivings of the practical mother. The second film, "Aparajito" (1956), follows the family to Benares, where the father makes a living from pilgrims who have come to bathe in the holy Ganges. The third film, "The World of Apu" (1959), finds Apu and his mother living with an uncle in the country; the boy does so well in school he wins a scholarship to Calcutta. He is married under extraordinary circumstances, is happy with his young bride, then crushed by the deaths of his mother and his wife. After a period of bitter drifting, he returns at last to take up the responsibility of his son.

This summary scarcely reflects the beauty and mystery of the films, which do not follow the punched-up methods of conventional biography but are told in the spirit of the English title of the first film, "The Song of the Road." The actors who play Apu at various ages from about 6 to 29 have in common a moody, dreamy quality; Apu is not sharp, hard or cynical, but a sincere, naive idealist, motivated more by vague yearnings than concrete plans. He reflects a society that does not place ambition above all, but is philosophical, accepting, optimistic.

This summary scarcely reflects the beauty and mystery of the films, which do not follow the punched-up methods of conventional biography but are told in the spirit of the English title of the first film, "The Song of the Road." The actors who play Apu at various ages from about 6 to 29 have in common a moody, dreamy quality; Apu is not sharp, hard or cynical, but a sincere, naive idealist, motivated more by vague yearnings than concrete plans. He reflects a society that does not place ambition above all, but is philosophical, accepting, optimistic. He is his father's child, and in the first two films we see how his father is eternally hopeful that something will turn up--that new plans and ideas will bear fruit. It is the mother who frets about money owed the relatives, about food for the children, about the future. In her eyes, throughout all three films, we see realism and loneliness, as her husband and then her son cheerfully go away to the big city and leave her waiting and wondering.

The most extraordinary passage in the three films comes in the third, when Apu, now a college student, goes with his best friend, Pulu, to attend the wedding of Pulu's cousin. The day has been picked because it is astrologically perfect--but the groom, when he arrives, turns out to be stark mad. The bride's mother sends him away, but then there is an emergency, because Aparna, the bride, will be forever cursed if she does not marry on this day, and so Pulu, in desperation, turns to Apu--and Apu, having left Calcutta to attend a marriage, returns to the city as the husband of the bride.

Sharmila Tagore, who plays Aparna, was only 14 when she made the film. She projects exquisite shyness and tenderness, and we consider how odd it is to be suddenly married to a stranger. "Can you accept a life of poverty?" asks Apu, who lives in a single room and augments his scholarship with a few rupees earned in a print shop. "Yes," she says simply, not meeting his gaze. She cries when she first arrives in Calcutta, but soon sweetness and love shine out through her eyes. Soumitra Chatterjee, who plays Apu, shares her innocent delight, and when she dies in childbirth it is the end of his innocence and, for a long time, of his hope.

Sharmila Tagore, who plays Aparna, was only 14 when she made the film. She projects exquisite shyness and tenderness, and we consider how odd it is to be suddenly married to a stranger. "Can you accept a life of poverty?" asks Apu, who lives in a single room and augments his scholarship with a few rupees earned in a print shop. "Yes," she says simply, not meeting his gaze. She cries when she first arrives in Calcutta, but soon sweetness and love shine out through her eyes. Soumitra Chatterjee, who plays Apu, shares her innocent delight, and when she dies in childbirth it is the end of his innocence and, for a long time, of his hope. The three films were photographed by Subrata Mitra, a still photographer who Ray was convinced could do the job. Starting from scratch, at first with a borrowed 16mm camera, Mitra achieves effects of extraordinary beauty: Forest paths, river vistas, the gathering clouds of the monsoon, water bugs skimming lightly over the surface of a pond. There is a fearsome scene as the mother watches over her feverish daughter while the rain and winds buffet the house, and we feel her fear and urgency as the camera dollies again and again across the small, threatened space. And a moment after a death, when the film cuts shockingly to the sudden flight of birds.

I heard a distant echo of the earliest days of the filming, perhaps, when Subrata Mitra was honored at the Hawaii Film Festival in the early 1990s, and in accepting a career award he thanked, not Satyajit Ray, but--his camera, and his film. On those first days of shooting it must have been just that simple, the hope of these beginners that their work would bear fruit.

What we sense all through "The Apu Trilogy" is a different kind of life than we are used to. The film is set in Bengal in the 1920s, when in the rural areas life was traditional and hard. Relationships were formed with those who lived close by; there is much drama over the theft of some apples from an orchard. The sight of a train, roaring at the far end of a field, represents the promise of the city and the future, and trains connect or separate the characters throughout the film, even offering at one low point a means of possible suicide.

The actors in the films have all been cast from life, to type; Italian neorealism was in vogue in the early 1950s, and Ray would have heard and agreed with the theory that everyone can play one role--himself. The most extraordinary performer in the films is Chunibala Devi, who plays the old aunt, stooped double, deeply wrinkled. She was 80 when shooting began; she had been an actress decades ago, but when Ray sought her out, she was living in a brothel, and thought he had come looking for a girl. When Apu's mother angers at her and tells her to leave, notice the way she appears at the door of another relative, asking, "Can I stay?" She has no home, no possessions except for her clothes and a bowl, but she never seems desperate because she embodies complete acceptance.

The relationship between Apu and his mother observes truths that must exist in all cultures: how the parent makes sacrifices for years, only to see the child turn aside and move thoughtlessly away into adulthood. The mother has gone to live with a relative, as little better than a servant ("they like my cooking"), and when Apu comes to visit during a school vacation, he sleeps or loses himself in his books, answering her with monosyllables. He seems in a hurry to leave, but has second thoughts at the train station, and returns for one more day. The way the film records his stay, his departure and his return says whatever can be said about lonely parents and heedless children.

I watched "The Apu Trilogy" recently over a period of three nights, and found my thoughts returning to it during the days. It is about a time, place and culture far removed from our own, and yet it connects directly and deeply with our human feelings. It is like a prayer, affirming that this is what the cinema can be, no matter how far in our cynicism we may stray.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)