A LITTLE GOES a long, long way. So attests a song, though getting the knockout break is often as farfetched as fists raised at the moon. Talk about the ongoing euphoria over Pacman’s punches—to the tune of more than two million dollars— and abject is the obvious about us: We are suckers for sharks. Who wants to be a small fry forever, anyway, and runs against the tide where the jackpot—dangled in the glut of game shows and talent searches— looms like a hook for our fish-mouths?

A LITTLE GOES a long, long way. So attests a song, though getting the knockout break is often as farfetched as fists raised at the moon. Talk about the ongoing euphoria over Pacman’s punches—to the tune of more than two million dollars— and abject is the obvious about us: We are suckers for sharks. Who wants to be a small fry forever, anyway, and runs against the tide where the jackpot—dangled in the glut of game shows and talent searches— looms like a hook for our fish-mouths?

Tragic but true: the worth of one’s hard work and dedication to duty can scarcely keep one’s neck above water. In this country, deliverance from dire straits comes more often and only when one slaves it out overseas. Or wins the lotto. Where good fortune is synonymous to a gamble, small wonder why many go with the flow of corruption and pyramid schemes.

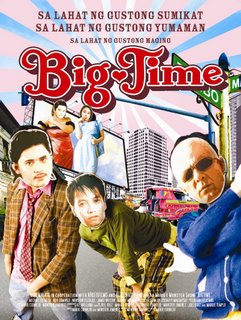

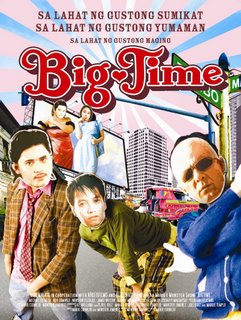

Nobody, indeed, wants to be stuck in the shallows when the rest are breezing through the crests in the ocean. That, in a nutshell, is what Big Time, a small-budgeted Filipino film (having its last day today at SM Cinema), brings to the fore. With astonishing insights into the Pinoy soul, edgy does it as it packs a tidal wave of a wallop into our Third World theatre of the absurd.

Where Peque Gallaga’s Pinoy Blonde sank under the unwieldy cargo of Quentin Tarantino’s influence, Big Time plumbs the depths of the Filipino experience, at once grim and graceful with humor, and dares to be ingenious in unfurling its sails for international ports of call. In the tradition of heist-centered capers like Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, this indie production earns its own howls by the originality of its own outrage.

Rated A by the Film Ratings Board, Big Time also boasts of a cornucopia of fine performances by Michael de Mesa, Nor Domingo, Winston Elizalde, Jamie Wilson, and Joanne Miller. But what makes this little magic of a movie smells of a Sundance hit is its storytelling audacity (it already won Best Screenplay, aside from Best Sound in last year’s Cinemanila festival of independent films).

Raring to raise the bar of their petty felony, two hustler-friends found themselves caught, along with a megastar-wannabe, in the web of a crime lord’s son who brews up a scheme out of his father’s shadow by staging his own kidnapping. Pretty simple plot, that. But it’s a testament to the kick-ass sense and sensibility of the film’s creative tandem (director Mark Cornejo and co-writer Coreen “Monster” Jimenez) that the film is buoyant with a crosscurrent of characters stirring up a sea of pop-culture references— from showbiz to mulcter’s monkey business to  prayer rallies— with the ease of a ripple. It’s like seeing Lino Brocka’s claustrophobic world once again, but this time through the amused eyes of Ishmael Bernal that could have winked at the film's in-your-face vibe worthy of an MTV.

prayer rallies— with the ease of a ripple. It’s like seeing Lino Brocka’s claustrophobic world once again, but this time through the amused eyes of Ishmael Bernal that could have winked at the film's in-your-face vibe worthy of an MTV.

Brace for a headshake and a chuckle out of this dark comedy where the crux of the narrative takes place in a safe house where discarded mannequins share space with a cabal of dreamers. Where the joke of a wish or prayer denied resounds with a thud softened only by the sound of Apo Hiking Society crooning, “Pumapatak na naman ang ulan sa bubong ng bahay”. Where ghosts of the hopeful speak, wryly so, of what could have been from their lives no more substantial than a puddle of rain.

(From my column So To Speak in Sun.Star Cebu)

EVERY WRITER worth the ground under his feet knows losing one's head in the ether of imagination is a risk too real for comfort. It's a tightrope act no less of a daze than keeping one's toehold on truth between the devil and the deep blue sea: escapism from and engagement with the world. Indeed, to find a room of one's own is also to run the peril of shutting one's self off till the walls crumble on creativity's reason for being-- awareness, empathy, discovery.

EVERY WRITER worth the ground under his feet knows losing one's head in the ether of imagination is a risk too real for comfort. It's a tightrope act no less of a daze than keeping one's toehold on truth between the devil and the deep blue sea: escapism from and engagement with the world. Indeed, to find a room of one's own is also to run the peril of shutting one's self off till the walls crumble on creativity's reason for being-- awareness, empathy, discovery.

"A retreat from the world can be a perilous journey.

" So asserts the title of Jonathan Rosen's essay printed in The New York Times:

THE JEWISH MYSTICS believed that God, in order to create the world, had to make himself smaller. I consoled myself with this notion when my daughter was born and I had to move my office out of the large spare bedroom and into the maid's room.

Long before my move, I'd been keenly aware of the weird expansions and contractions necessitated by creative life, particularly the painful paradox that to write about the world, you have to retreat from it. Not completely, of course. I like the way Walt Whitman described himself: "Both in and out of the game, and watching and wondering at it."

Even with that credo in mind, writing is lonely work. For Virginia Woolf it wasn't glorious travels or vast experience but a room of one's own that the writer needs most. She knew you can only advance by retreating. Of course her maid's room probably had a maid in it, which no doubt took the edge off the solitude.

But all writers wind up metaphorically in the servants' quarters. When you write, you're taking orders from somewhere — a higher (or at least a lower) power — and the work isn't always pretty. I was appalled to discover that my first novel, "Eve's Apple," was about a woman starving herself and a man madly in love with her and morbidly fascinated by her illness. It is not the novel I thought I would write, not how I wished to enter the world. But I was forced to say, like Prospero pointing at Caliban, "This thing of darkness I acknowledge mine."

The inner journey is often a perilous one. Even the divine contraction was fraught with danger. The mystics concluded that because God had to shrink in order to make room for the world, he was no longer all-powerful. The vessels intended to receive his glory broke, scattering divine sparks all over the place and introducing imperfection into the world, presumably explaining why the world is full of flawed characters and horrific plot twists. All I had to do was install a second phone line.

But even if I do not have to worry about my superabundant energy overflowing inadequate containers (if only I did!), stepping out of life can be disorienting. It can even seem a little humiliating, especially in New York City, with the busy world streaming past my windows. I became keenly aware of this when, along with our daughter, my household acquired a nanny. She only works three days a week, but her presence has made me awkwardly aware of just what my writing day looks like.

Our nanny's husband is a welder and works outdoors in all kinds of weather. What does she think when she sees me, a grown man who goes to work in his bedroom slippers? Or when I wander out of my little room at midday, while my daughter is taking a nap, to lie on the couch with a book? Or if I sit by the window staring out for a while? Or if the need to figure out a certain scene or a certain sentence — or the need to escape from a certain scene or a certain sentence — drives me from my desk over to, say, a box of cereal for a late-morning snack.

Keats referred to the poet's “diligent Indolence,” a state of suspended activity necessary for creativity. On days when I'm really diligent, I might even take a nap, not unlike my daughter who, after 12 hours at night, still needs a little supplementary sleep to feel refreshed. Play, after all, is hard work; Anna Freud called play the work of children. And perhaps of writers, too.

Play is work; inside is outside; indolence is activity. One might add that the imaginary is real, and introspection is actually a form of social research. No wonder I have to take a nap from time to time. Eventually one must put aside the paradoxes and the explanations and simply write.

But even then I find that the paradoxes make their way into the writing. "The Talmud and the Internet," my most recent book, despite its title and subject, wound up having at its core a description of my two grandmothers. In a book about harmonizing unlikely elements, nothing challenged me more than my own contradictory inheritance: one of my grandmothers lived a long and prosperous American life; my other grandmother was murdered by Nazis.

Each life and death pointed to radically different conclusions about the nature of the world, of human conduct. The best I could do was put them side by side and, in the manner of the Talmud, let them each stand as point and counterpoint, neither dissolving into the other. I let my grandmothers take their place alongside all the famous figures in my book, Talmud sages and great writers and historical figures, because without that personal element my public speculations seemed weirdly abstract. There's always a piece of writing that for me must be close to home, the string that binds the balloon to the earth.

I was at some level as embarrassed to find myself writing about my grandmothers as I was to find myself writing about a self-starving woman. Where was the grand picaresque American adventure I had always imagined I would create? What were my grandmothers doing in the middle of everything, calling me home? The wonderful thing about writing is that it forces you to confront yourself in a way you don't usually have to. That is, needless to say, also the terrible thing.

I used to waste my energy envying an earlier generation of Jewish writers, children of immigrants who seemed umbilically linked to authentic experience I was born too late for. They were fueled by a world-conquering hunger that made their protagonists born-again Don Quixotes. Well, as Jorge Luis Borges wrote, "The world, unfortunately, is real; I, unfortunately, am Borges." This is a universal problem, not a literary one. Everybody has to find his own voice, whether or not he is a writer.

This is why all the arcane things a writer discovers about his craft aren't really arcane. Everybody has to make the inner descent into himself, everybody needs metaphors to live by, and everybody has to order the chaos of experience into some kind of narrative, if only in the depths of dream-fashioning sleep. In that regard, the writer who stays home is really a kind of everyman. There should be more novels about him.

He is also something of an immigrant himself, exploring the world and groping for the words that will help him master it. And staying at home has taught me something else: my daughter is a kind of immigrant, too. I hear her as I write this; she is in her highchair in the kitchen, just outside my door, being fed her lunch. She is learning to say brief truncated words: "nana" for banana; "mih" for milk. Soon enough she will know my language so well that the physical world she is on such intimate terms with may seem abstract, reaching her through a muffling amnion of mediating words.

Inevitably my home is becoming a sort of melting pot for my daughter. She cannot go through life yanking the phone off the hook, pointing at things and screaming if she doesn't get them. She cannot (very important) push open the door of my maid's room whenever she wants.

And though this process of assimilation is necessary, it has a small element of sadness in it for me. Because I so love her untutored, marveling attitude to the world. I love her deep attach-ment to sunlight, the way she pokes the water in her bathtub to test its properties, the way she gapes at the mystery of a face, laughing in amazement.

"Not in entire forgetfulness and not in utter nakedness but trailing clouds of glory do we come," Wordsworth wrote. For him God himself was "our home," the Old Country where we all once lived and for which we all secretly pine. On earth we learn a new language. But if we manage to keep the trace of an accent from the mysterious place we once inhabited, so much the better for us.

"Not in entire forgetfulness and not in utter nakedness but trailing clouds of glory do we come," Wordsworth wrote. For him God himself was "our home," the Old Country where we all once lived and for which we all secretly pine. On earth we learn a new language. But if we manage to keep the trace of an accent from the mysterious place we once inhabited, so much the better for us.

Certainly all my favorite writers have retained their attitude of wonder. And I think this matters to me most about writing, beyond history and politics, plot and structure, the literal and symbolic. Of course one wants all those things, too. But there is something much more primitive and simple and elusive that lies at the core of writing that has to do with the sheer mystery of the created world. For me it is what links a cave painting to a page of "Ulysses.”

Perhaps it is the need to approach this mystery that explains why I am a grown man who stays home with the nanny when other people are going to work. And why, as I sit in the maid's room proudly overhearing my daughter speak her first words in my language, I find myself hoping I will capture a few forgotten elements of hers.

SOME SQUIRM at the sight of spiders. Creepy, they say. Never mind if those crawlies are nowhere near the tarantula's level.

SOME SQUIRM at the sight of spiders. Creepy, they say. Never mind if those crawlies are nowhere near the tarantula's level.

Then again, I'd stick my neck out to vouch for one of the world's most overlooked natural wonders, a perfect model for order and harmony, wrought out of such silken concentration worthy of a Zen master, with such craftmanship packed at once with lethal potency and fagility enough to give monks a run for their meditation, an ode to solitude: the spider's web.

No wonder, a character in Bergman's film Through a Glass Darkly had visions of God as a giant spider.

Caught in his own fantasy, my eldest son Golli (short for Gabriel Ollivan) thinks he is Spider-Man. God bless the power of imagination. Stuck myself in the web of my own flights of fancy, I hope he'd grow up to understand and empathize in due time his father's own thread of longing for fortitude and grace. Here's my first published poem (which I have recently revised since it was printed in the Philippines Free Press, 4 June 1994 issue) shortly after my creative writing fellowship at the 1994 National Writers Workshop in Dumaguete:

SPIDER SENSE

He thinks of how a spider makes its web, how the web is torn/ by people with brooms, insects, rapacious birds; how the spider/ rebuilds and rebuilds, until the wind takes the web and breaks it and flicks it into heaven's blue and innocent immensity.. - Stephen Dobyns

Windowing

the whiteness

of the wind,

the blind's incandescence

straight from the storm's eye as I

see a web, unspidered.

Fled from the dead, I hear

the mourners in the living room chanting my name.

My shadow looms in a corner,

reaching for cobwebs while

a whorl of gossamer

whirls in my head, darkly,

lest they'd see me, skull-shaven

or with hairs graying in

the wee hours

of awareness.

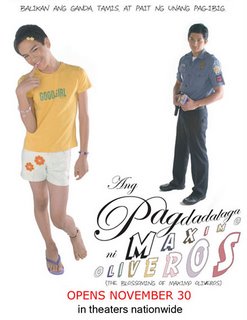

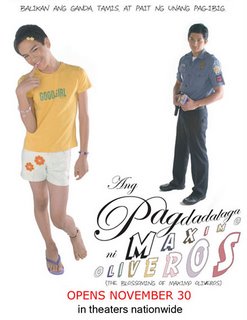

INDIE PAVES THE WAY. As big studios continue to raise a stinker, squirting puss at the eyes of Filipino filmbuffs, upcoming independent artists are thumbing down their noses at the dinosaurs in the movie industry. Look how the past three years saw independent films raising the stakes for the world to see. Digital fares like Lav Diaz’s 10-hour epic Ebolusyon ng Isang Pamilyang Pilipino, Mario O'Hara's Babae sa Breakwater, Maryo de los Reyes' Magnifico, Cesar Montano's Panaghoy sa Suba, Rico Ilarde’s Sa Ilalim ng Cogon, Mark Reyes’ Last Full Show, Khavn de la Cruz’ Lata at Tsinelas, and Brillante Mendoza's Masahista drew critical raves abroad. And then came one gem titled Ang Pagdadalaga ni Maximo Oliveros. Hands down, it's the best Filipino film of 2005, the banner year of indie filmmaking.

INDIE PAVES THE WAY. As big studios continue to raise a stinker, squirting puss at the eyes of Filipino filmbuffs, upcoming independent artists are thumbing down their noses at the dinosaurs in the movie industry. Look how the past three years saw independent films raising the stakes for the world to see. Digital fares like Lav Diaz’s 10-hour epic Ebolusyon ng Isang Pamilyang Pilipino, Mario O'Hara's Babae sa Breakwater, Maryo de los Reyes' Magnifico, Cesar Montano's Panaghoy sa Suba, Rico Ilarde’s Sa Ilalim ng Cogon, Mark Reyes’ Last Full Show, Khavn de la Cruz’ Lata at Tsinelas, and Brillante Mendoza's Masahista drew critical raves abroad. And then came one gem titled Ang Pagdadalaga ni Maximo Oliveros. Hands down, it's the best Filipino film of 2005, the banner year of indie filmmaking.

Here's a reprint of my review titled "A miracle called Maximo" in my opinion column for Sun.Star Cebu (6 December 2005):

CUTTING THROUGH a slum colony, a hearse adorned with wreaths passes along a mound of garbage near a bridge. The camera, panning along the sludgy river below, zooms in on its surface with its surfeit of the city’s trash. A hint of purple ripples across: a flower floating among the flotsam.

This is how Ang Pagdadalaga ni Maximo Oliveros begins. Gritty, yes, but gracefully does it cut into a scene of an assured hand, that of the limpwristed protagonist, picking a discarded orchid from the rubbish. With flair, the pubescent Maximo puts the flower at his ear and sashays through the squalor of his squatter’s neighborhood. Aptly, it might as well be a metaphor for this movie: how it rises or blooms above the country’s rotting celluloid industry. That independent filmmaking is blossoming hereabouts is nowhere more patent in the fierceness of panache and originality so striking about this cinematic gem directed by Auraeus Solito. A coming-of-age tale, it focuses on the gay Maximo caught in the crossroads between his fascination for an idealistic greenhorn cop in his neigborhood and his filial love for a family, the sort you’d like to spray insecticide at (the widower father is a small-time criminal like Maximo’s two elder brothers). But extra-ordinary is the way Solito’s deft hand transforms Maximo’s home out of its horrid circumstance with scenes iridescent with understated tenderness and humor, crackling under the family’s tough surface like stone flickering, as if its tough skin were made for spontaneous combustion.Not a spark of melodrama here, nothing overstretched. Not here are the run-of-the-mill grists for movies where the gay character providing the narrative ballast wallows in the banality of gender issues and all that hohum.

This is how Ang Pagdadalaga ni Maximo Oliveros begins. Gritty, yes, but gracefully does it cut into a scene of an assured hand, that of the limpwristed protagonist, picking a discarded orchid from the rubbish. With flair, the pubescent Maximo puts the flower at his ear and sashays through the squalor of his squatter’s neighborhood. Aptly, it might as well be a metaphor for this movie: how it rises or blooms above the country’s rotting celluloid industry. That independent filmmaking is blossoming hereabouts is nowhere more patent in the fierceness of panache and originality so striking about this cinematic gem directed by Auraeus Solito. A coming-of-age tale, it focuses on the gay Maximo caught in the crossroads between his fascination for an idealistic greenhorn cop in his neigborhood and his filial love for a family, the sort you’d like to spray insecticide at (the widower father is a small-time criminal like Maximo’s two elder brothers). But extra-ordinary is the way Solito’s deft hand transforms Maximo’s home out of its horrid circumstance with scenes iridescent with understated tenderness and humor, crackling under the family’s tough surface like stone flickering, as if its tough skin were made for spontaneous combustion.Not a spark of melodrama here, nothing overstretched. Not here are the run-of-the-mill grists for movies where the gay character providing the narrative ballast wallows in the banality of gender issues and all that hohum.

As written by Michiko Yamamoto (she who penned the simply magical film Magnifico), Ang Pagdadalaga… is a triumph in sidestepping the stereotypes even as it nimbly dances around and kicks headlong into the viewers’ hearts. “Passionate, fascinating and extraordinary,” so raves New York-based critic Godfrey Cheshire in his reviews for the New York Times and Village Voice. Small wonder why the Cinema Evaluation Board has thumbed it up and regarded it as “Rated A.”More than well-deserved, indeed, is the film’s cache of international accomplishments so far. Aside from being hailed as Best Film at the festivals in Montreal and Singapore, it also has the distinction of being the first Filipino masterpiece to be included for competition at the 2006 Sundance Film Festival.To watch this film is to see how Filipino filmmakers— despite the dross long after the likes of Gerardo de Leon, Lino Brocka and Ishmael Bernal are gone— continue to do wonders.

As written by Michiko Yamamoto (she who penned the simply magical film Magnifico), Ang Pagdadalaga… is a triumph in sidestepping the stereotypes even as it nimbly dances around and kicks headlong into the viewers’ hearts. “Passionate, fascinating and extraordinary,” so raves New York-based critic Godfrey Cheshire in his reviews for the New York Times and Village Voice. Small wonder why the Cinema Evaluation Board has thumbed it up and regarded it as “Rated A.”More than well-deserved, indeed, is the film’s cache of international accomplishments so far. Aside from being hailed as Best Film at the festivals in Montreal and Singapore, it also has the distinction of being the first Filipino masterpiece to be included for competition at the 2006 Sundance Film Festival.To watch this film is to see how Filipino filmmakers— despite the dross long after the likes of Gerardo de Leon, Lino Brocka and Ishmael Bernal are gone— continue to do wonders.

VERY BASIC. Or so Dr. Resil Mojares echoes, at the 2005 Cornelio Faigao Memorial Writers Workshop in Cebu, the smart-alecky point of a fellow writer who simplifies the complex world of a difference between prose and poetry. "Prose is planned parenthood," he grins, "while poetry is accidental pregnancy."

VERY BASIC. Or so Dr. Resil Mojares echoes, at the 2005 Cornelio Faigao Memorial Writers Workshop in Cebu, the smart-alecky point of a fellow writer who simplifies the complex world of a difference between prose and poetry. "Prose is planned parenthood," he grins, "while poetry is accidental pregnancy."

About that distinctive fissure or face-off in literature, Mark Halliday explains more in this reprint from The Georgia Review:"SOMETIMES Sometimes fatigue or a journal stuffed with bad poems throws us into poetry-dismay, even poetry-disgust, but poetry soon wins us back. A good poem comes along that is damned appealing; it has charisma, it has a peculiar panache, it cuts a new path through experience, it expresses - or it is - a new truth, or new edge of truth. Life is suddenly undreary. And this poem is so strangely sure of itself! Where did it get such nerve? It has a quality I will call arrogance.

A poem, just by being a poem, says ‘I am more significant than all your chatter, all your information, all your reports and articles, more significant even than all your stories, more important than any page of Crime and Punishment or Women in Love or Middlemarch - even, in a mysterious way, more important than each of these novels as a whole. You must gaze down into the well of me. You may never see to the bottom.’

The essential sign of poetry's arrogance is white space. Poetry takes unto itself the luxurious, ostentatiously high-class option of not reaching the right hand margin. Prose must pack itself into the common area, the second-class accommodations, filling the page all the way to the margin regardless of whether it's referring to the principles of Baroque architecture or the Meaning of Meaning or what some Hollywood star wore to a premiere. The unfilled part of a poem's page is the ornamental garden surrounding the castle of superior meaning. A poem says, ‘I can drape myself in white space like a mink coat. I stand apart from the mundane tide of utilitarian utterance. I create and require a respectful silence around me.’

The arrogance of poetry is titanically oppressive in the silence immediately after a poem’s last line. That silence stares at you. It says, ‘Do you or do you not get it.’ It says, ‘Do you love me? You should. If you don't, you've missed something. The problem is yours - some blindness, some crudeness, some insensitivity to nuance.’

If a person said that to you, or if a person’s way of falling silent implied that, you would respond energetically - you would walk out of the room, or laugh in the person's arrogant face, or ask intense questions, or express remorse. Like such a person, a poem refuses to be taken casually. If you do take a poem casually, you feel slothful, shallow, flippant - a feeling that is very different from thinking hard about a poem and deciding it is itself slothful, shallow, flippant. Fortunately, persons don’t often have the gall to say, ‘If you don't love me, the problem is yours.’ Poems say this every time.

Poems keep stroking their own hair. A poem is like the person at the table who won’t speak unless everyone else hushes to listen. A poem is like the person whose tone announces: Enough of your jabber. Now I shall speak words worth remembering. You should want to chisel these words in marble.

Poems keep stroking their own hair. A poem is like the person at the table who won’t speak unless everyone else hushes to listen. A poem is like the person whose tone announces: Enough of your jabber. Now I shall speak words worth remembering. You should want to chisel these words in marble.

Poetry’s demand for special attention is one aspect of its essential arrogance. Another is its pride in implication. A poem always knows - or carries - something it doesn't spell out. A poem is like someone who conveys crucial meanings with subtle changes of gaze and gesture, with eyebrows rather than words; a poem suddenly stares at you to see if you can meet its challenge. This gaze is charismatic - when it is not absurdly portentous. We are beguiled and enthralled by the poem’s sublime implicitness - when we are not irritated and repulsed.

Confronting a poem, we often have to work hard to decide whether its oddity or difficulty comes from a wonderfully forgivable, or from a repulsive arrogance. The arrogance of all poetry is tiring - like both good sex and bad sex.

Poems are mostly read by people already hooked on poetry. How does a novelist feel, reading a book of poems? The novelist may feel a puzzled respect for someone who doggedly writes a kind of literature unlikely to bring wealth or fame. At the same time, the novelist may feel annoyed when the poet offers such small things - coy, anemic perceptions and teasing metaphorical connections - as if each one were terrifically unusual - a day' s work! - enshrined by costly whiteness on all sides, commanding a hushed and riveted attention. The novelist has produced countless equally sharp images and insightful connections and richly evoked moments - hundreds in each novel! And the novelist has given these gifts to the reader without poetry's preening insistence that each morsel is a sublime Godiva truffle. The novelist may think the poetry is ‘good’ but that her own work by comparison is admirably unpompous and generous.

But Thomas Hardy, one of the few writers great as both poet and novelist, felt that greatness in poetry mattered more than greatness in prose. Isn't this an unreasonable bias?

But Thomas Hardy, one of the few writers great as both poet and novelist, felt that greatness in poetry mattered more than greatness in prose. Isn't this an unreasonable bias?

To be calmly sensitive and thoughtful each time a poem is in front of your eyes, but to turn away for rest and refreshment before either exhaustion or cynicism sets in. This nearly angelic response is humanly possible, but it is amazingly hard to sustain.

Poems crowd toward you like the shades of the underworld when Odysseus visits; they crave the hot blood of attention.

Or they crowd toward you like refugees mobbing a United Nations worker who dispenses far too few bags of grain from the back of a truck.

Notice the inconsistency of that simile with the analogy of a poem's being like a proud high-chinned person requiring a respectful hush around his or her augustness. On the level of self-presentation, each poem is that dignitary; meanwhile, on the practical level, seen from outside, each poem is more like a famine victim in danger of being trampled beneath the feet of its fellow poems, all famished for the reader's ration of attention.

The poem seems not to have noticed its actual social situation. Picture a crowded, deafening cocktail party; in the middle of the room stands the poem, addressing itself to anyone and everyone, not even shouting, regardless of whether anyone listens. In real life this is a kind of madness. In art, it is the arrogance of art...

JACKPOTS happen like this: Just when boredom starts to kick in while you're idling through the mall, you spot a book sale. See what I got, scoured from the shelves in one of the stores at Robinson's Cebu. A handful of second-hand gems priced at 10 pesos each---whoa!---here are my first four book acquisitions in 2006:  Slouching Towards Bethlehem. Upon its publication in 1968, this book of essays confirmed Joan Didion as one of the most prominent writers on the literary scene. Her unblinking vision and deadpan tone have influenced subsequent generations of reporters and essayists, changing our expectations of style, voice, and the artistic possibilities of nonfiction. "In her portraits of people," The New York Times Book Review wrote, "Didion is not out to expose but to understand, and she shows us actors and millionaires, doomed brides and naïve acid-trippers, left-wing ideologues and snobs of the Hawaiian aristocracy in a way that makes them neither villainous nor glamorous, but alive and botched and often mournfully beautiful....A rare display of some of the best prose written today in this country."

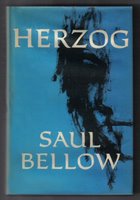

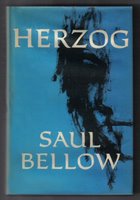

Slouching Towards Bethlehem. Upon its publication in 1968, this book of essays confirmed Joan Didion as one of the most prominent writers on the literary scene. Her unblinking vision and deadpan tone have influenced subsequent generations of reporters and essayists, changing our expectations of style, voice, and the artistic possibilities of nonfiction. "In her portraits of people," The New York Times Book Review wrote, "Didion is not out to expose but to understand, and she shows us actors and millionaires, doomed brides and naïve acid-trippers, left-wing ideologues and snobs of the Hawaiian aristocracy in a way that makes them neither villainous nor glamorous, but alive and botched and often mournfully beautiful....A rare display of some of the best prose written today in this country." Herzog. Nobel Prize winner Saul Bellow's "Herzog" received the International Literary Prize in 1965; the story of Moses E. Herzog, a confused intellectual suffering from the breakup of his second marriage, the failure of his life and the specter of growing up Jewish in the middle part of the 20th century.

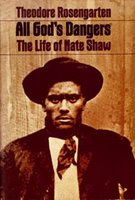

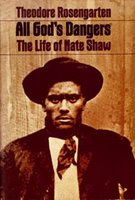

Herzog. Nobel Prize winner Saul Bellow's "Herzog" received the International Literary Prize in 1965; the story of Moses E. Herzog, a confused intellectual suffering from the breakup of his second marriage, the failure of his life and the specter of growing up Jewish in the middle part of the 20th century. All God's Dangers. This triumphant National Book Award recipient assembled from the 84-year-old sharecropper's oral reminiscences is the plain-spoken story of an "over-average" man who witnessed wrenching changes in the lives of Southern black people – and whose unassuming courage helped bring those changes about. "There are only a few American autobiographies of surpassing greatness....Now there is another one, Nate Shaw's," raves The New York Times. "When, finally, this big book is put down, one feels exhilarated," agrees Studs Terkel. "This is an anthem to human endurance."

All God's Dangers. This triumphant National Book Award recipient assembled from the 84-year-old sharecropper's oral reminiscences is the plain-spoken story of an "over-average" man who witnessed wrenching changes in the lives of Southern black people – and whose unassuming courage helped bring those changes about. "There are only a few American autobiographies of surpassing greatness....Now there is another one, Nate Shaw's," raves The New York Times. "When, finally, this big book is put down, one feels exhilarated," agrees Studs Terkel. "This is an anthem to human endurance."

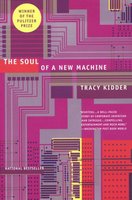

The Soul of a New Machine. Winner of the Pulitzer Prize, and selected by the Modern Library as one of the100 best nonfiction books of the 20th century. Computers have changed since 1981, when Tracy Kidder indelibly recorded the drama, comedy, and excitement of one company's efforts to bring a new microcomputer to market. What has changed little, however, is computer culture: the feverish pace of the high-tech industry, the mystique of programmers, the go-for-broke approach to business that has caused so many computer companies to win big (or go belly up), and the cult of pursuing mind-bending technological innovations. By tracing computer culture to its roots, by exploring the "soul" of the "machine" that has revolutionized the world, Kidder succeeds as no other writer has done in capturing the essential spirit of the computer age.

The Soul of a New Machine. Winner of the Pulitzer Prize, and selected by the Modern Library as one of the100 best nonfiction books of the 20th century. Computers have changed since 1981, when Tracy Kidder indelibly recorded the drama, comedy, and excitement of one company's efforts to bring a new microcomputer to market. What has changed little, however, is computer culture: the feverish pace of the high-tech industry, the mystique of programmers, the go-for-broke approach to business that has caused so many computer companies to win big (or go belly up), and the cult of pursuing mind-bending technological innovations. By tracing computer culture to its roots, by exploring the "soul" of the "machine" that has revolutionized the world, Kidder succeeds as no other writer has done in capturing the essential spirit of the computer age.

RANDOM ACCESS of odds and ends, this harbor of poetry and prosaic renderings about everything from my recurrent flights of fancy. Here, too, are wrapped drafts of inspiration from various sources I take upon myself to keep against the barbaric invasion of oblivion. This blog, dear eavesdropper, comes in the heels of my other online journal solely devoted to my essential identity as a Cebuano writer called Beso Bisdak (http://www.bisdakobenieta.blogspot.com). Wherever the port of call, let us-- you and me-- stay anchored on our common task as long as we live: To remember. To celebrate. To believe.

RANDOM ACCESS of odds and ends, this harbor of poetry and prosaic renderings about everything from my recurrent flights of fancy. Here, too, are wrapped drafts of inspiration from various sources I take upon myself to keep against the barbaric invasion of oblivion. This blog, dear eavesdropper, comes in the heels of my other online journal solely devoted to my essential identity as a Cebuano writer called Beso Bisdak (http://www.bisdakobenieta.blogspot.com). Wherever the port of call, let us-- you and me-- stay anchored on our common task as long as we live: To remember. To celebrate. To believe.

prayer rallies— with the ease of a ripple. It’s like seeing Lino Brocka’s claustrophobic world once again, but this time through the amused eyes of Ishmael Bernal that could have winked at the film's in-your-face vibe worthy of an MTV.

prayer rallies— with the ease of a ripple. It’s like seeing Lino Brocka’s claustrophobic world once again, but this time through the amused eyes of Ishmael Bernal that could have winked at the film's in-your-face vibe worthy of an MTV.